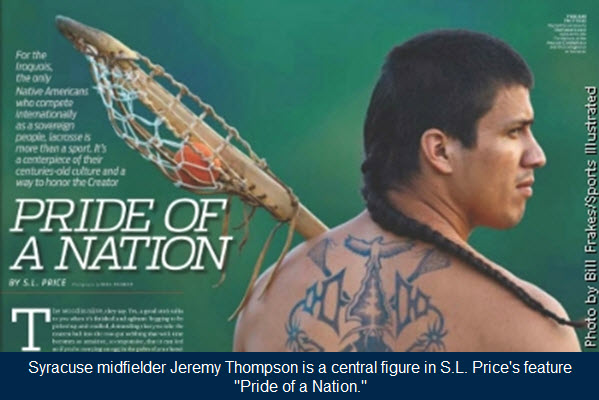

This article is from 2010 and deserves to be re-published. It was originally published in Sports Illustrated. The author, S.L. Price is currently working on a book titled “Lacrosse in America”.

The wood is alive, they say. Yes, a good stick talks to you when it’s finished and agleam: begging to be picked up and cradled, demanding that you rake the nearest ball into the cow-gut webbing that with time becomes so sensitive, so responsive, that it can feel as if you’re carrying an egg in the palm of your hand. But Alf E. Jacques can hear the wood long before that, when what will become a lacrosse stick still resembles a shepherd’s crook, and the drilling and sanding and shellacking are yet to be done. This one? He can all but feel it breathe beneath his blade.

But then, Jacques expected as much. A master stickmaker whose workshop squats behind his mother’s house on the Onondaga reservation, just outside Syracuse, N.Y., he selected, steamed, bent and began air-drying a prime batch of hickory poles 28 months ago. Usually a year is long enough to make a good lacrosse stick, but Jacques was taking no chances; he wanted these poles cured to perfection for this mid-June afternoon, when he would sit at his cooper’s bench, take a draw-shave in hand and begin shaping the six-foot defensive sticks for the competition to come.

“This is for the Iroquois Nationals,” the 61-year-old Jacques says. “Nobody else gets one. Every four years I make at least six D-sticks for them.” He laughs. “And they usually save them for when they play the Americans.”

On July 15 the Nationals are scheduled to open the 2010 lacrosse world championships against host England in Manchester, but that’s no sure thing. For 27 years the team representing the Iroquois—the confederacy of Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca and Tuscarora nations—has been the sole Native American entity to compete internationally, traveling on Iroquois (or, in their language, Haudenosaunee, meaning People of the Long House) passports and balancing lacrosse’s prep school vibe with an aura of history and mystery and loss. But last week, just days before their scheduled departure, the Nationals were told by officials of the U.S. State and Homeland Security departments that they would not be allowed to exit and enter the country on those documents.

The Iroquois in turn rejected an offer to travel on U.S. passports. “We are representing a nation, and we are not going to travel on the passport of a competitor,” said Tonya Gonnella Frichner, an Onondaga lawyer and a representative to the U.N. Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. As of Monday night neither side had budged, raising the possibility that for the first time since 1990, the world championships would be contested without the game’s inventors.

This might seem like a mere bureaucratic snafu, but it represents a serious threat to both the tournament and the Iroquois nation. Despite drawing from a population of only about 125,000 people scattered across northeastern North America and despite lacking the financial clout of lacrosse’s international powers, the Iroquois have finished fourth in the last three world championships, and they figured to enter the 30-nation 2010 competition as true contenders. The Nationals are also the Iroquois’s most public expression of sovereignty, of their long-held belief that they are an independent people. Beating mighty Team USA or defending champion Canada in Manchester would be sweet, of course. But the mere hope that the Nationals would enter the United Kingdom on their own terms, bless the tournament with a traditional tobacco-burning ceremony and then take the field against the world’s best would make claiming the championship almost beside the point. “Winning is not the end-all,” says Sid Jamieson, who coached the first Nationals team in the early 1980s. “Just being there is a victory.”

Let ’em know you’re there, they say. Having a presence, showing the world that they still exist, is a constant theme with the Iroquois, and few things express it more memorably than a jab with a wooden stick. “I remember getting checked, and my arm would go numb, just go limp,” says former Syracuse player John Desko, who now coaches the Orange and who coached Team USA at the 2006 world championships. In the Nationals’ match against host Canada that year, defender Mark Burnam, now a Nationals assistant coach, says he used his pole to “slash people on purpose and let them know that they were going to get slashed every time. I’d throw pokechecks, and that thing don’t bend. [Opponents] would shy away from me. I don’t blame them. The thing is like a friggin’ weapon. It nearly kills you.”

The advent of the aluminum-shaft, plastic-head, nylon-web stick in 1970 might have been the single greatest spur to lacrosse’s growth, but it marginalized the wooden shaft; leagues now ban it, coaches discourage it, parents see one and complain. Native American or not, every player in NCAA lacrosse uses what Oren Lyons, a member of the Onondaga council of chiefs, calls “Tupperware.” And if the Nationals play in England, most of their stickheads will be plastic too.

Yet the wooden stick remains central to the Iroquois religion and culture: Males are given a miniature version at birth, sleep with their playing sticks nearby or even in bed, and take one with them into the grave. In international field lacrosse the Iroquois are the only players who still use wood, and while the sight of it might be unwelcome to their opponents, it gives even victimized apostates a thrill. During a hotly contested game between the Nationals and Team USA at the 1999 under-19 world championships in Adelaide, Australia, players from Australia, Canada and England began chanting, “Bring out the woodies!” Three Nationals defenders swapped their Tupperware for hickory to roars from the crowd.

“When those six-foot wooden sticks come out,” says Iroquois attackman Drew Bucktooth, “they know we’re there.” That’s why, a month before the start of the 2010 world championships, Sid Smith felt compelled to make his way to Jacques’s workshop. Smith, a 23-year-old defender from the Six Nations reservation in Ontario, led two NCAA championship teams and was a one-time All-America at Syracuse; he capped his college career by stripping the ball and setting up the game-winner in overtime of the 2009 title game, against Cornell. Smith grew up playing almost exclusively with plastic and has never used a six-foot wooden stick in competition. But he wants one now.

Jacques isn’t ready for Smith’s request: Each stick is different, and players always want a batch from which to choose. But Smith is less patient than most Nationals (“I want to win all the championships I can,” he says), and this year’s roster is coming in thin and disorganized. He’s going to need help.

“I’m here [again] next Thursday,” Smith says to Jacques. “Will you have it done by then?”

“I’ll try,” Jacques says. “I’ll get done as many as I can—maybe four. I got other work, too. I was thinking, like, July. I wasn’t thinking now.”

“Even one,” Smith says. “I’ll take whatever one you finish.”

The game is older than the country , they say. It goes back 900 years, maybe more; what’s certain is that Native Americans in the Great Lakes region invented lacrosse, began the massive gatherings involving anywhere from 100 to 1,000 men playing one game over days on a field with goals spread as far as two miles apart. But the ceremony known as Dey Hon Tshi Gwa’ Ehs (To Bump Hips) was less a substitute for war than a way to honor the Creator. When an Iroquois dies, the first thing he does after crossing over is grab the stick laid in his coffin. “You’ll be playing again that day,” says Lyons, an Onondaga faith keeper, or protector of Native traditions, “and you will be the captain.”

In the late 19th century a Montreal dentist named William George Beers, following the usual white man’s practice of appropriating all things Indian, codified the modern rules of field lacrosse, giving it a time limit and replacing the leather ball with a rubber one. By 1880, after it was discovered that some Native Americans had accepted pay to play the purportedly amateur sport, all Natives were banned from international competition by the sport’s governing body. Shut out from the 10-on-10 field game at the highest level, Natives competed in obscurity until box lacrosse—a faster, more violent, six-on-six version invented in 1930 to take advantage of unused hockey rinks—swept across the reservations.

What ensued over the next decades is one of sport’s shadow tales, unseen by a world entranced by Ruth and Unitas and Ali, played out by hard, proud men steeped in privation. Their names are famous only on reservations in New York and Canada: unstoppables such as Oliver Hill, Ross Powless, Edward Shenandoah. The Mohawk great of the late 1940s, Angus Thomas? He had a shot so hard, they say, that it killed two goalies. Banned from box leagues for more than a year after one of the deaths, Thomas played his first game back against the Onondagas in the old Akwesasne box near St. Regis, N.Y.—with 19-year-old Lyons between the pipes. Lyons, armored with two chest protectors and a wad of sliced fan belt, saw Thomas wind up and heard the ball sizzle just before it cracked into his midsection, snapping three ribs, leaving him down and breathless for 20 minutes. But Thomas didn’t score. “There was no way the ball was going to go in,” Lyons says.

Some non-Natives tried coming over from their elegant, wide-open field game to slum in the dusty outdoor box on the Onondaga reservation, where cross-checking was legal and anyone lingering along the boards was begging to be hurt. “I wanted to play their game their way, but I wasn’t tough like that,” says Roy (Slugger) Simmons Jr., who played for Syracuse in the 1950s under his father, the legendary Roy Simmons Sr., and later coached the Orange to six national championships.

The scene at Slugger’s first box game was cockfight crazy: Native women ringing the boards, shaking the chicken-wire fencing as he passed with the ball, stopping their unnerving screams just long enough to spit at him. After a line change Simmons dropped to the bench and was approached by an old Indian named Percy Lazore, who had played against Simmons’s dad in the 1920s and ’30s. “Roy, you mad,” Lazore said.

“Yeah, Percy, look at all the gobs of spit on me,” Simmons said. “What the hell’s wrong with them?”

“Roy, they spit on good players. What you worry about is if they don’t spit on you.”

To the wider world, NFL legend Jim Brown is the most famous Syracuse lacrosse player, often deemed the greatest of all time, supposedly never knocked off his feet. But on the reservation they remember the pickup game in 1957 in which the 155-pound Irving Powless, a future chief, sent the 230-pound, new-to-the-box Brown tumbling with a brutally precise hip check. “Brown never left his feet the rest of the day,” Simmons says. “He just destroyed them.”

By then Lyons had become one of the trailblazers of the route from the rez to Syracuse. He co-captained the Orangemen’s undefeated 1957 team with Brown and Simmons, earning All-America honors in front of the net with his deft hands and sawed-off goalie’s stick. He graduated, worked in New York City as a greeting-card illustrator and was inducted into the Lacrosse Hall of Fame. He became a faith keeper in ’67, moved back to Onondaga in ’70 and taught U.S. history at SUNY Buffalo. In 1977 he designed the Iroquois passport and verified its acceptance on a group trip to Switzerland.

The Iroquois’s independent streak and their players’ lack of field experience earned them a cool reception when they tried out for U.S. or Canadian teams. A few Iroquois became stars in the college game, but as a group they “were kind of snuffed out,” Simmons Jr. says. Decades in the box had cut the nation off from its own game; generations of Iroquois had never learned team defense. When, in 1983, Simmons asked Lyons to bring a squad to Baltimore for a series of international friendlies, he heard one of history’s saddest replies. “We don’t have a field team,” Lyons said.

Still, along with Tuscarora stickmaker Wes Patterson, Lyons cobbled together a disparate mix of box, high school and college players for the inevitable thrashing. Syracuse crushed the first Nationals 28–5, and Hobart handled them 22–14. But a spark caught. “The guys didn’t like to get beat,” Lyons says. The Iroquois hosted a special tournament in Los Angeles before the 1984 Olympics and earned their first victory, over the English national team. They went to England the next year, won several more games and lost only one. Two years after that Lyons got a 3 a.m. call from England: The century-old ban was lifted. The international federation had accepted the Iroquois as a full member nation. “It was our game,” Lyons says. “So here we are 100 years later, back up again.”

Box lacrosse remains the game of choice for most Iroquois, so it’s no shock that their best international result has been indoors: second place, ahead of Team USA, in the last two world box championships. But a growing stream of Division I stars, such as Loyola’s Gewas Schindler and Syracuse’s Sid Smith, Brett Bucktooth, Cody Jamieson and Jeremy Thompson, has made the Nationals an increasing threat on grass, and it’s not as if outdoor play had been excised from the Iroquois DNA. Throughout the year “medicine” games are played for the health of all players, the traditional way: Two poles are jammed in the ground on each end to serve as goals, an unlimited number of males from ages seven to 70 ranges about, and the first team to score a certain number of goals—sometimes three, sometimes five—wins. Any male can call for a medicine game to deal with personal strife; a runner goes out to contact the players, and the food is gathered and a deerskin ball obtained that day. The caller doesn’t play, but he keeps the ball. “The ball is the medicine,” Lyons says.

The Iroquois don’t like talking in detail about the medicine game, at least not with outsiders. But 20 years ago Nationals offensive coach Freeman Bucktooth called for a medicine game on The Greens at Onondaga to help him and a friend fight an illness. “It helped,” Bucktooth says, so he renews it each year. “Whatever illness you have, it pushes it away. It’s amazing how well it cures you.”

Only wooden sticks are allowed in medicine games. Familiarity, the long break-in time and the sheer beauty of a prized lacrosse stick partly explain why some Iroquois cry when one splinters. But a deeper reason for their grief is the belief that the stick is a gift from Mother Earth, that a living thing died to make it and that its spirit has been transferred to the Iroquois player, who honors the tree’s sacrifice by playing humbly, calmly, “in a more spiritual manner,” Jacques says. “Nobody likes a dirty player, and the energy from that tree is transferred to that player who knows how to use it.”

One evening last January, Lyons, soon to be 80, stick in hand, hustled along the darkened hallways of the Onondaga Nation Arena. A $7 million facility that opened in 2001, Tsha’Honnonyendakhwa’ (Where They Play Games) is the modern centerpiece of the Onondaga reservation and a far more practical statement than the tattered billboard on I-81 whose faded message reads, WE THE INDIGENOUS PEOPLE OWN THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE!

Not that Lyons doesn’t believe that. Two 1794 treaties, one of them brokered by George Washington—the one that still pays each Iroquois descendant five yards of calico yearly—are the Iroquois’s legal basis for sovereignty and the reason Syracuse police have no jurisdiction on the reservation. Casinos? Establishing a casino would entail asking the U.S. government’s permission. Oren Lyons, for one, has never asked the U.S. permission for anything.

He stopped in the lobby, at the trophy case, and pointed at its most eye-catching display, a lone blue warmup jacket with red-and-white piping on the shoulders, hanging on a wire hanger. There’s no placard, no list of accomplishments, no explanation. “Here’s Lee,” Lyons said.

He was one of the best ever, they say. That mattered to Leroy (Lee) Shenandoah; whether he was doing ironwork or playing lacrosse or serving in the Army, nothing less than excellence would do. “I used to be afraid to fry him an egg—everything was perfection,” says his sister, Beulah Powless. “And his temper: If [his wife] Deena didn’t iron the pants just right? He’d rip them in half. She didn’t get upset. She knew.”

From the late 1950s through the ’60s, Shenandoah put his ferocity and skill to work in the box for the Onondaga Warriors, precursors to today’s Senior B Can-Am Lacrosse League entry, the Redhawks. Shenandoah was a lean and fast force who could shoot, dodge, pass and defend. He could power or slash to the goal. “He was like [Alex] Ovechkin: He could score, he could run you over,” says Freeman Bucktooth. “And when he spoke, you listened.”

It was easy, once he was dead, to make Shenandoah a symbol of the tragic Native experience, illustrating all the bad that could befall an Indian who ventured off the rez. After dropping out of high school at 16 and becoming a high-iron foreman on construction sites at 17, Shenandoah joined the Army and became so accomplished a Green Beret that he marched in the honor guard at President Kennedy’s funeral. Less than a decade later, in March 1972, he died at 32 after being shot five times and kicked by Philadelphia police, who claimed he had attacked them and resisted arrest—until film of the incident surfaced that raised questions about the police version of the events. The two officers responsible were never charged with a crime.

“The war’s not over,” Lyons says with a smile. “Not by a long shot.”

These days Shenandoah’s legacy burns most fiercely with the Iroquois Nationals. He had a way of looking out for people, sometimes even white opponents in the box. “He knew I was naive and a target, and many times he could’ve leveled me,” Slugger Simmons says. “But he’d come up and say, ‘Roy, I’m doing you a favor: Keep your head up.'” Shenandoah was close to the Bucktooths and kept an eye on young Freeman, first babysitting him, then teaching him all he knew about the game. Nobody, Freeman says, had better all-around skill, and from Shenandoah he learned most of what he knows about winning face-offs, the subtleties of stickhandling, the value of spying on the opposing goalie during warmups. “And he could fight,” Bucktooth says. “Nobody would mess with him.”

No wonder, then, that fisticuffs became Freeman’s trademark too. For a decade he led the Senior B League in scoring; he once rang up 19 goals in a game. But ask about him and the first thing everyone mentions is how he brawled in the box as a teenager, cutting through other teams’ enforcers, leaving a line of 25-year-old men facedown, needing stitches. Bucktooth played two years at Syracuse for Slugger Simmons, who knew the effect that Freeman’s “Geronimo look”—high cheekbones, shock of black hair—could have on nervous whites. Whenever the team bus rolled onto a new campus, Simmons made sure that Bucktooth was first man off. “I’ll scare ’em,” Freeman would say.

College life didn’t take, but Bucktooth carried Shenandoah’s perfectionist bent into adulthood. He put in 80 hours a week climbing poles, repairing high wire for Niagara Mohawk Power. He dragooned his sons into helping him build their log-cabin home with 140 precisely notched timbers—no nails. He overhauled the structure of kids’ leagues at Onondaga to expose hundreds of young Iroquois to more and better competition and coached them at every level from Peanuts to Juniors, traveling with the six-year-olds into Canada one year, taking the U-19s to Australia another, making his voice heard on the Nationals’ governing board.

Knowing that college lax was one sure route out of the rez, Bucktooth insisted on teaching field techniques in the box, guiding all the Iroquois boys to cradle and pass and shoot off both wings. And always in his mind he would hear Shenandoah’s voice, preaching toughness, a hunger to win every ground ball. “We could never get through a scrimmage, couldn’t go three minutes without the whistle stopping and him instructing us: It should be done right. Practice how you play in the game,” says Freeman’s third son, Brett. “And if you’re playing against your best friend and you don’t cross-check him or you let him pick up a ground ball, he said, ‘I don’t care if he’s your best friend: Go hit him.’ The game’s meant to be tough.”

Of course, all four Bucktooth boys and their countless cousins—”Go out in the woods,” says Jacques, “and you’ll step on one”—lived Freeman’s philosophy. This year, with Freeman coaching the offense, Brett at midfield and 29-year-old Drew at attack, the Nationals will again have Bucktooth marks all over them. The family’s influence is pervasive; any afternoon at Onondaga Nation Arena, Freeman can still be found roaming the box during youth practices, even down to the Peanut division, where four- to six-year-old boys pump their little legs up and down the floor. Brett and other Nationals vets will be there, too, coaching their own sons; every few minutes another kid will be sent sprawling by a vicious slash. The men give each boy a moment to lie there, then tap a foot with a stick: That’s enough. Let’s go.

One June day Beulah Powless is sitting out in the lobby, waiting for her six-year-old great-grandson, Gabe, to finish Tykes practice. She’s speaking about her brother, Lee Shenandoah, nearly 40 years gone: how his two children have scattered, how the family received a small settlement from the city of Philadelphia but no apology, how Lee came to their mother, Gertrude Shenandoah, in a dream. But then Gabe runs up asking for snack money, and she recalls a moment from two weeks before, when he got leveled by a shot to the neck in a game against Allegheny. She went over to the team bench where Gabe sat stewing and asked if he was O.K., and he gave her a look that was so pure, so Lee, that for just a second it was as if her brother were still living.

“I’m going back in,” Gabe said, “and I’m going to fight.”

There’s no team like it, they say. When the Iroquois Nationals travel, overseas especially, they carry a mystique born of Hollywood imagery and pure novelty. So English schoolkids ask Nationals coaches, “How does the smoke get out of your house? Do you still hurt people?” and Japanese opponents treat the players like rock stars, and reporters flock to see the exotics in action. Thus is delivered the only message that matters. “We’re still here,” Smith says.

“The Nationals are showing the world that we are on the map,” Jacques says, his voice rising. “When you say Indians, Native Americans, what pops into mind? Out west, in a tepee, on a reservation, alcohol, drug abuse, drain on society, poverty, uneducated—beaten down. How many negatives can they put on this group of people? So to have a positive there on the world stage is such a big thing for us.”

But the Nationals’ singularity stems not just from their role as standard-bearers for all Native Americans; there are three roster spots for players from any other tribe, and this year’s squad includes a Cherokee goalie and an Ojibwa defender. The Nationals also operate in ways that can mystify their own staff, let alone sympathetic outsiders. “They’re an extremely funny group, sarcastic, love to talk and have fun and compete,” says Roy Simmons III, Slugger’s son, director of lacrosse operations at Syracuse. “But every time I walk away, I’m always scratching my head, wondering what happened.”

As the youngest member of one of sport’s enduring coaching dynasties, Roy III grew up proud of his family’s 50-year relationship with the Iroquois and couldn’t have been more honored when the Nationals asked him last summer to join the coaching staff. But in early June, he and Bill Bjorness, the 2006 Nationals coach, who had been a member of the coaching staff since 1994, resigned because of frustration over management moves that had reduced training time, paralyzed the selection process and left the team scrambling on the eve of the worlds.

The Americans have beaten the Nationals in the last five world championships, Smith says, because they’re “usually bigger, in a little better shape, [have] a lot more players to choose from—and [are] a lot better organized.” This year the contrast has been starker than usual. Team USA set its 23-man roster last November and scheduled five tough exhibition games. The Nationals didn’t announce their roster until June 20, by which time they’d had only two scrimmages, none since February. They finally held another training camp in the first week of July.

The delays didn’t allow newly appointed general manager Ansley Jemison much time to arrange airline tickets and visas to Great Britain; when the U.S. dropped its passport bomb, there were only three days left before the Iroquois’s planned departure, and what could have been a challenging problem became a crisis. But long before the travel mix-up, the Iroquois’s concern with self-definition had taken a toll on their lacrosse program.

An imperative to include players representing all Six Nations increased political maneuvering during the Nationals’ selection process, and last December—after months of tryouts—the Iroquois Traditional Council made a devastating decision: For the first time in Nationals history, a player’s Native lineage would be a major issue, decided strictly through his mother. Once-acceptable adoptees, players with only small traces of Indian blood and offspring of mixed marriages involving non-Native mothers were rejected. The Nationals’ midfield was gutted when five players were cut loose for reasons of lineage.

Just as curious, some prime Iroquois players didn’t try out for this year’s team, opting to devote themselves to family, work or their box teams. “There are players who should be on this team who aren’t,” Freeman Bucktooth says. “[Defender] Marshall Abrams—an All-America at Syracuse—chose not to play. I’m upset that some didn’t try out, and I’m upset that some guys got cut. I told everybody: There are three guys who should be on the team because they add speed, and that’s something we lack.”

For someone like Roy Simmons III, who comes from a white, win-at-all-costs culture, such decisions seem inexplicable. “Here I am stupidly thinking we’re going to send the best team,” he says, “and it’s not really going to happen.” But though many of the coaches—such as Mark Burnam, who saw his brother bounced from the squad—share Simmons’s frustration over the Traditional Council’s ruling, they don’t have the luxury of walking away. “I have to respect that,” says Jemison. “That’s the stance of the coach and the entire staff: We respect our tradition, and that’s what we’re going to go by. We can’t bellyache, because then we’re cutting our own throats.”

What he means is, at a time when the Iroquois are struggling to protect their language and culture from the enticing encroachments of American life, when each Iroquois lacrosse player who goes to Syracuse represents, yes, a success story but also a flight risk—a man in danger of losing his Native ways—things such as lineage do mean more than the world’s biggest lacrosse tournament. Iroquois tradition requires that chiefs make each decision with an eye on its impact seven generations from now (hence the N7 logo on Nationals gear); there’s a reason Lyons calls Nike the team’s partner, not sponsor. Today’s Iroquois fear being subsumed, fear Culture USA more than Team USA, and the message We are still here will mean little if the weis allowed to grow fuzzy.

“There’s a lot more weighing on us,” Jemison says. “It’s our identity.” Which, not by accident, dovetails with the larger Iroquois lacrosse paradox: Spiritually and socially the game is central in ways inconceivable for any sport in any other culture—but winning isn’t. Some players, such as Smith and Cody Jamieson, may indeed be motivated to win titles, but the typical Iroquois sees lacrosse as the place to present himself to the Creator, not prove himself No. 1.

Desko, the Syracuse coach, understands this, at least enough to make allowances. Last fall his dazzling new midfielder, Jeremy Thompson, announced that he would miss more than a week of training because he had to fast for four days—no food, no water—in an Onondaga cleansing ritual that leaves participants weak and sometimes delirious. “And I’m sitting here going, Whooo. Interesting,” Desko says. “But another coach? ‘Screw that, fast on your own time! Miss practice and you’re done!’ But Jeremy’s not doing it to take the day off. He’s doing it because he wants to be a better Iroquois.”

Thompson feels many of the pressures facing young Natives who try, as he puts it, to “live in two worlds.” His great-grandfather was a chief, and Jeremy grew up steeped in tradition. “We weren’t allowed to have the girls touch our wooden sticks; it’s a medicine game for men, not women,” he says. “If it was on the ground, my mom would leave it there.”

With his summer job tutoring Onondaga kids in their Native tongue and his plans to resurrect the adolescent rite of passage known as vision quest—not to mention the long ponytail trailing down his back—Thompson, 23, seems the picture of Native American piety. But living according to his ideals has been a struggle. When his family moved from the Mohawk reservation to Onondaga, he was in the fifth grade and could barely read or speak English; he struggled in school and by 15 began bingeing on alcohol. Why not? That’s what many of the men on the rez do.

Only 11.5% of Native Americans graduate from college. “We’re always thinking back home is more important,” Thompson says. “That’s the problem we have nowadays in getting kids off and going to college. They don’t want to leave the family or the reserve, and another big part is the drugs and alcohol. They have no way of finding themselves. We don’t have that connection, the role models, somebody there to direct them the right way.”

After poor grades derailed his dream of playing for Syracuse, Thompson won two junior college national titles at Onondaga Community College and beefed up his transcript enough to gain admission to Syracuse last fall. But he also boozed plenty, and his dream of playing for the Orange with his younger brother, Jerome, died when Jerome ran into academic trouble. “He quit,” says Jeremy. “He couldn’t handle school.” Then Jeremy’s longtime girlfriend, whom he had planned to marry this summer, broke up with him.

“I’m a better person because she did that,” he says. “I’m thankful. I realize what I put her through all those years I was out drinking, doing what I wanted to do. She’s a good woman, traditional, Long House, had all those qualities that I want in a woman. And I shot that out the door.”

Thompson started to get clean 18 months ago, but last fall the constant toggle between all-Native life on the rez and all-American college life sparked a short relapse. After that, however, he learned that negotiating both worlds, working toward a degree but not forsaking his traditions, was actually doable. “It’s not like the old days,” he says. “We have to go out.” Loneliness helped him see it clearly: He could be the example he never had. This fall he’ll be a senior at Syracuse, on track to earn a degree in communications.

“I’m on the verge,” he says. “I found out these things are always going to pull at you, but I’m really digging in now; I feel like my days of fooling around are done. I’m down to business with learning our ways, our ceremonies, and lacrosse started to help me out. It’s a sport I can always go to for medicine, for relief, to have fun.

“Another thing I found out about lacrosse: I’m doing it for the younger ones behind me now. I look at my life—how it was taken, where I fell off my track—and I want to be there and have a program for kids to find themselves, their spirituality and find what they were put here for. That way, they’re ahead of the game.”

He’s still young, they say. Quick of mind, light on his feet, zipping around town in a Prius, Oren Lyons begins his ninth decade utterly unimpressed by his own stature. One morning last January a teenager walked into a Syracuse restaurant carrying a defender’s stick and, when introduced to Lyons, clearly didn’t know that the man in front of him was a chief, a caretaker of the Iroquois way, a voice on indigenous and climate issues who has been heard by the United Nations General Assembly and Bill Moyers and the bright lights who gather each year in Davos. That was fine: Lyons had more important things to talk about.

“Don’t forget to pokecheck,” he said. “Any ball on the ground is yours, you know.”

Because before he was anyone, Lyons was one of the best goalkeepers ever, and even old goalies can’t help bossing defenders around. In 1996 he traveled with the U-19 Nationals to Edogawa, Japan, for the world championships. He was in the locker room before an exhibition against a college team when coach Freeman Bucktooth jokingly suggested he suit up. Lyons didn’t laugh. He borrowed some equipment, grabbed his wooden stick and headed for the goal.

He was 66 years old. The day was witheringly hot. Though manning the larger field net, Lyons positioned himself with one hand on his stick, box style. And then they started to come, the shots: breakaways, one-on-ones, rocketing in after every fake and juke the young athletes could muster. But for one half Lyons stood in, erasing four decades until he was at Syracuse again, with Jim Brown and Slugger Simmons ranging upfield. Lyons whipped his stick around like a nunchaku, deflected ball after rock-hard rubber ball, stuffed one point-blank missile after another as sweat poured down his back.

“I’ve never seen a goalie play like that, with one hand on his stick in a six-foot net,” says Drew Bucktooth. “Jumping up with his elbow, making saves? And he didn’t have arm pads, so he’s making saves with bare arms. He had to have 12, 15 saves and gave up just one goal. Had to be 100 degrees that day. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

So, yes, Lyons is nearly evangelical when he speaks of the Onondagas’ new partnership with a Swedish firm to make vertical greenhouses for cities, and dead serious about the Iroquois’s role as a ravaged planet’s prime steward. “The Haudenosaunee are the ones who give thanks to the earth,” he says. “We take care of it, and we’re doing it very well here. When you look around the world today and see what’s going on? We’re in deep s—. People have no idea. But we know.”

Lacrosse is the Creator’s game, a way to show gratitude for this same earth, and Lyons expects progress there too. The passport problem only energized him, made him sure that “either way, we still win,” he says. If the Nationals are forced to stay home, they become a rallying point for indigenous rights; if the U.S. clears them to travel on their own documents, Lyons says, “it’s going to be a recognition.” And if the Iroquois play in England this week, Lyons is sure their days of finishing fourth will end. “We will medal,” he says. And for anyone who figures the recent turmoil makes the Nationals ripe for defeat, he serves up a challenge.

Like Thompson, Lyons wears his hair in a long braid. But now he brings up an old Iroquois warrior style, a shaved head with a small patch of hair on the back. Asked the native term for it, he says, “Scalplock. To make it easier for them to scalp you.” As his guest’s bewildered, sputtering reply stalls at “but why would… ?” his eyes gleam. Lyons grins and nods as the trap snaps shut.

“You want it?” he says. “You come and get it.”